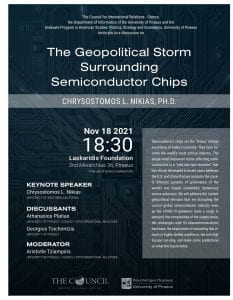

USC President Emeritus C. L. Max Nikias delivered a major lecture, “The Geopolitical Storm Surrounding Semiconductor Chips,” at the historic library of the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation in Piraeus, Greece.

Nikias said that the growing “cold war-style tensions” between China and Western democracies is rooted in starkly different systems of governance and is the single most important factor looming over the world’s semiconductor industry.

“To put it bluntly, it is democracy versus autocracy.”

Athanasios Platias of the University of Piraeus who was on an academic panel offering questions and commentary following the lecture said, “what emerged from today’s talk is the important point that whoever controls technology – especially semiconductor chips – has tremendous advantages enabling them to dominate the global economy as well as international politics.”

The manufacture of semiconductor chips has become the most important industry in world today, Nikias said. “No other industry has the same mix of hard science, brutal capital intensity and fiendish complexity.”

Advanced semiconductor chips have many critical military applications and are a key ingredient in the Internet of Things. They are the foundation for the artificial intelligence revolution, 5G networks, robotics, telemedicine, remote work and education, virtual and augmented reality, and streaming entertainment. Today, household appliances, home security systems and even toothbrushes can contain chips. Nikias said that ten years ago a car might have had 10 or 20 chips but most cars built today contain hundreds. The new Ford Mustang Mach-e has almost 3,000 chips.

“Chips are the brains behind everything,” he said.

While disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a worldwide semiconductor chip shortage, exploding demand for the chips was already straining an intricate semiconductor supply chain that stretches around the world.

“The design, testing, verification and manufacturing of the most advanced chips depends on a relatively small number of companies in the U.S., European Union, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan,” he said. The exotic materials and components needed may cross dozens of international borders and chips go through a thousand or more exacting steps before they are ready for customers. “It costs anywhere from 20 to 50 billion dollars to build a state-of-the-art chip fabrication factory, or fab.”

“We are currently in a golden age of chip design as the quest for faster, cheaper, more memory and lower power semiconductor chips with AI applications added on top continues unabated. Designers are squeezing multiple chips together massively in three dimensions with AI applications driving the architecture.”

The smallest features that can be made on chips determine how advanced they are. Today’s state-of-the art chips are five nanometers with production of three-nanometer chips expected later this year.

“Three nanometers! That’s the thickness of six silicon atoms,” he said.

The iPhone 13 is powered by a five-nanometer chip with 15 billion transistors. While designed by Apple, the chip is manufactured by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC. TSMC makes more than 90 percent of the world’s sub ten-nanometer chips with South Korea’s Samsung making the rest. Intel, the U.S. company that once dominated the chip industry, is scrambling to catch up. China, despite massive investments, is unable to make the most advanced chips and spends about $300 billion a year importing them, more than any other import including oil.

But Nikias said China has made dramatic advances in many other technology areas such as telecommunications, green energy, quantum computing, commercial drones and advanced batteries. China’s juggernaut company, Huawei, is the dominant manufacturer of the telecommunications gear used for the roll out of 5G networks. Until recently, the U.S. dominated telecommunications technologies.

In 2017, the Trump Administration, worried about advanced semiconductor chips migrating to China’s military, moved to cut off the supply of cutting-edge semiconductors to Huawei. The Biden Administration continued and expanded the policy so that restrictions now affect at least 60 Chinese companies. The U.S. has enlisted its European and Asian allies and companies have little choice but to go along with the policy because the U.S holds intellectual property rights to many of the key underlying technologies needed for advanced chips.

Last year, the commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command warned that China might invade Taiwan to gain control of its semiconductor industry. A senior U.S. security expert said that “whoever controls the design and production of these microchips will set the course for the 21st century.”

Nikias pointed out that free markets in democratic societies allowed semiconductors and other high-tech industries to flourish. But in the past two decades, autocratic China has demonstrated an astonishing ability to innovate and has made rapid advances in many technology areas.

Nikias estimated that China was no more than 8 to 10 years behind the U.S. in semiconductors but ended his talk on an optimistic note.

“Democracies by their very nature … always delay reacting to a threat but when they do, they make great leaps,” he said. “Technology enabled by democracy is how we will flourish and ensure the freedom that we cherish.”

The lecture was sponsored by the Council for International Relations – Greece (CFIR-GR) and the Department of Informatics and the Graduate Program in American Studies – Politics, Strategy and Economics at the University of Piraeus.